|

The following are questions commonly posted on our discussion boards,

along with answers and advice from responding members. In many cases,

member answers have been expanded on from other sources, and relevant

links have been addedfor more information. These answers are meant only

as a helpful guide and a resource for further information; each individual

situation is unique and may need a tailored solution. Your treating psychiatrist

is always a good person to ask when you have specific questions pertaining

to your own case.

If you don't find what you're looking for here, please visit the Schizophrenia

Main Discussion Board (see the righthand menu column on the Schizophrenia.com

homepage ) and post your question. Our members are usually very generous

with their advice and support.

Index of Questions:

Diagnosis and Treatment:

How is schizophrenia diagnosed? How can I tell if

someone has schizophrenia?

What to do if you suspect you or a loved one may have

a psychiatric disorder

What if my family member refuses to see a doctor?

What to do after recieving a diagnosis - how you can help

What is the prognosis? How likely is it that a person

with schizophrenia will ever have a "normal" life?

How is schizophrenia treated?

What to expect after going on medication

What if I can't afford prescription medications?

Working with the psychiatrist

Hospitalization - when and why is it necessary?

The hospital

experience

Choosing a facility

Concerns of families

My son (or daughter) is over the legal age of 18 and the

doctors won't share with me information on his treatment (due to current

laws). What can I do to help my son/daughter, or sister/brother?

How can I help my loved one get the best care

possible?

Why won't my loved one stick to their treatment?

Coping With Schizophrenia:

How do I understand and deal with the symptoms?

(Delusions; Voices/Hallucinations;

Anger/Irritability/Mood swings; Violence

and Abuse; Paranoia; Suicidal

Thoughts and Tendencies; Apathy/Lack of Motivation;

Emotional Flatness and Social Withdrawal)

How Can I Help Someone Who's Depressed?

Why Is Depression So Common Among Schizophrenia Patients?

Possible

causes of depression

How to cope and

where to get help

What are the chances of relapse? How can you plan for

a relapse situation?

How do I explain the illness to family, close friends,

and others?

Living With a Severe Mental Illness - Practical Matters:

Planning for the future - issues for caregivers

and resources to help

Federal Aid and Funding Programs

Health Insurance and Aid

Housing concerns - if your loved one can't live at

home

Job and School Issues - can a person with schizophrenia

go back to work?

How can I help a family member who's been arrested?

How is schizophrenia diagnosed? How can I tell if someone has schizophrenia?

There is currently no physical or lab test that can absolutely diagnose

schizophrenia - a psychiatrist usually comes to the diagnosis based

on clinical symptoms. What physical testing can do is rule out

a lot of other conditions (seizure disorders, metabolic disorders, thyroid

disfunction, brain tumor, street drug use, etc) that sometimes have

similar symptoms.

Current research is evaluating possible physical diagnostic tests (such

as a blood

test for schizophrenia, special

IQ tests for identifying schizophrenia, eye-tracking,

brain

imaging, 'smell

tests', etc), but these are still in trial stages at only a few

universities and companies and are not yet widely used. I t will likely

be a few years before these on the market, and adopted by hospitals,

etc.

People diagnosed with schizophrenia usually experience a combination

of positive

and negative symptoms. These may include (but are not limited to)

racing or uncontrollable thoughts, uncontrollable mannerisms, talking

to yourself, paranoia, hallucinations or delusions, sensing that people

are following or talking to you, insomnia. The Symptoms

and Diagnosis section of this website may help you identify some

of your own symptoms, or the symptoms of someone close to you; however,

only a psychiatrist can make a diagnosis and start a treatment program.

If the symptoms are bothersome, debilitating, or harmful, please make

an appointment with your doctor and/or a psychiatrist.

The best places for schizophrenia diagnosis are the new early psychosis

and schizophrenia diagnosis and treatment centers that are beginning

to be launched worldwide. See our Worldwide

list of early psychosis/schizophrenia diagnosis and treatment clinics

and contact them if you, or someone you know, may be developing schizophrenia.

They have the most intensive testing process and can help get early

treatment (which improves changes of a good outcome).

What to do if you suspect you or a loved one may have a psychiatric

disorder:

The best places for schizophrenia diagnosis are the new early psychosis

and schizophrenia diagnosis and treatment centers that are being offered

worldwide. See our Worldwide

list of early psychosis/schizophrenia diagnosis and treatment clinics

and contact the center closest to you, if you or someone you know, may

be developing schizophrenia. They have the most comprehensive psychiatric

evaluation process and can help get early treatment (which improves

chances of a good outcome).

If you are not close to these early treatment centers or university-associated

psychiatric hospitals (click for list) , then the next thing you

might try is make an appointment with a qualified psychiatrist with

experience with psychosis and schizophrenia. See our section on Finding

and Working with a Psychiatrist (click here) for more information

on how to find a good one.

Another approach is to start with your primary care physician, and

get a full check-up and evaluation to rule out some other common neurological

disorders. Some tests that you might expect include an EEG, MRI, or

PET scan to rule out seizure disorders, and some lab tests to determine

pituitary and thyroid function. The doctor will listen to what you have

to say, hear about what difficulties you're having, and recommend a

course of action. This may be a referral to a psychiatrist. If you are

having trouble finding a good psychiatrist, again see "Finding

and working with the psychiatrist" section of this FAQ guide

for ideas.

It's a good idea to prepare materials and questions to take with you

to your appointments. Keep

a journal of symptoms, odd or troubling behaviors, psychotic episodes,

and anything else that you want your doctor to know about. Make a list

of questions that you want your doctor to answer. "Choosing

the Right Mental Health Therapist" (information provided by

the U.S. organization SAMHSA) has an easy-to-follow procedure list for

appointments, as well as some suggestions for questions you might ask.

What if my family member refuses to see a doctor?

Many people with schizophrenia are literally unable to see that there's

anything abnormal about them (this is commonly called 'lack of insight'

or 'poor insight'). It's almost a hallmark characteristic of the disorder,

like memory loss is for Alzheimer's disease. There are several physical

explanations for impaired awareness - the important thing to realize

is that your relative is most likely not being purposely obstinate,

difficult, or defensive when they deny their symptoms and refuse help.

This, however, leaves you as a concerned family member in an awkward

and extremely frustrating position. Current U.S. laws make it very difficult

to get help for someone who actively refuses it - someone may be actively

psychotic and in desperate straits, but still not considered a serious-enough

threat to themselves or others to merit involuntary hospitalization.

This is a constant source of trouble for families dealing with mental

illness. Visit the Treatment Advocacy Center website to look up state

laws on mental illness

The best course of action depends on the type and severity of symptoms.

If the symptoms are worrisome but not absolutely harmful yet, try locating

a mental health professional or a social worker who is familiar with

dealing with psychiatric disorders. They can discuss your relative's

behavior with you, and brainstorm the best way to get him/her help.

Options will vary from state to state, based on state law. In some areas,

you can call a crisis unit (look in the telephone book or call the hospital)

that will send an evaluation team, and maybe instigate a 72 hour psych

hold. Contact a local NAMI chapter

or call their helpline (1-800-950-NAMI) to look up resources in your

area.

Family members at schizophrenia.com have firsthand experience of what

has worked for them, and what you might do to help your situation. See

their suggestions

and advice on the schizophrenia.com website.

When patients are provided with full and accurate information for understanding

their illness and its treatment, sometimes their insight may improve.

You as a caregiver can play an important role by providing this information,

and presenting it in as optimistically as possible. See 'How

Caregivers Can Help a Relative Accept Their Illness'.

It can be very frightening to go through what your loved one is experiencing,

and a lot of people are hesitant to seek treatment because they are

afraid of being hospitalized. If you can, reassure your loved one that

if treatment is started eary enough, hospitalization is probably not

necessary. Emphasize that medication can make a huge difference in the

way they are feeling.

If the symptoms are very severe, your best option is to persuade a

hospital ER or the police department that your loved one is in grave

danger of harming him/herself or others. Although this might be absolutely

clear to you and other family members, the current strictness of legislation

places a very narrow definition on what counts as "harm to self

or others." Try and become familiar with what the criteria is ahead

of time, so that you can choose the right words to describe the situation.

If the hospital agrees that an involunatry admittance is necessary,

they will begin a three-day (or maybe less, depending on hospital policy)

psych hold. Without a court order, they are not permitted to hold anyone

involuntarily for longer. Talk to the treating physicians about how

to start court proceedings, or see your options for 'Assisted

Treatment' (this can include benevolent coersion, conservatorship

or guardianship, conditional release, outpaitent commitment, or an extended

voluntary commitment).

An Advanced Psychiatric Directive is also an option to discuss during

times when the ill person is in control and in a reasonable frame of

mind. This legal document allows the person with the illness to dictate

what actions should be taken on their behalf (including appointing another

person to make treatment decisions) if they should become unable to

make decisions for their own well-being. Bear in mind that Advance Directives

are not appropriate for all, or maybe even the majority, of people with

schizophrenia. In order for a Directive to be an empowering rather than

a coercive tool, the person who prepares the document for themselves

must have the skills and the social support to make beneficial decisions.

For more information, and for downloadable documents to help prepare

an AD, see the Advanced

Psychiatric Directives section of the Bazelon Mental Health Law

Website.

If the person has EVER violently threatened or actively harmed you,

another person, or themselves, call 911 or an emergency room immediately.

Violence against family members of the mentally ill is a reality, and

you need to protect yourself and everyone by getting your loved one

committed.

What to do after recieving a diagnosis - how you can help:

Whatever diagnosis is given, whether it is schizophrenia or something

else, know that there are many many patients and families out there

with the same questions, concerns, and problems that you face. There

is a wealth of information and support available to you. Here are some

things to try first:

1. Educate yourself and other family members as much as you

can about the illness, the treatments, and long-term prospects. Greater

understanding can help alleviate fears and can make communication, treatment

programs, and day-to-day coping much easier. See

Recommended Books for a list of helpful, reviewed reading material.

There is also a wealth of online information to read here at schizophrenia.com

(where we have over 12,000 pages of information on schizophrenia) and

other websites. Other web sites include that have some good information

include:

NAMI - National Alliance

for the Mentally Ill

MentalHealth.com

- free encyclopedia of mental health information created by Canadian

psychiatrist Dr. Phillip Long.

British

Columbia Schizophrenia Society - excellent resources for family

members

National Institute

of Mental Health - concise overview of different disorders, diagnoses,

treatments, options, and resoureces

Rethink - UK mental

illness charity - wealth of information for patients and family on disorders,

coping, practical matters, etc.

Check out our full list of web-based resources,

including organizations and online reading material

Also check out our online PDF reference library,

with links to the most helpful pdf documents on mental illness and related

issues. Ideal for printing for your own reference files, or passing

out to family/friends/teachers/employers.

2. Watch and Listen to our archives

of internet-based audio and video files on schizophrenia, mental

illness, and related issues. Good files to start with include:

--Schizophrenia Introduction and Overview - An

Educational Video (Schizophrenia Society of Canada)

--Schizophrenia - Second Chances - public radio

program covers the personal experiences of schizophrenia, how to help

people who don't understand they have schizophrenia, and how dramatic

advances in schizophrenia research are providing new hope for people

suffering from the disease.

--Schizophrenia: Treatment, Access, Hope for the

Future? - public radio progam invites a panel of experts to discuss

current research, treatment options, and impact on family members.

3. Build a support network as soon as you can of other families

with similar experiences. The discussion boards at schizophrenia.com

are a good place to start, but a local support group can be a long term

source of relief and resource for you during difficult times. The

National Alliance for the Mentally Ill has local chapters in every

U.S. state - visit their website and find one near you. Also, consider

taking a Family-to-Family class (also through NAMI), a free 12-week

education course designed for (and taught by) family caregivers of people

with severe mental illness. This class is highly recommended by many

members of schizophrenia.com. See the Family-to-Family

website for more program information and class schedules.

4. Find the mental health support resources in your area. Search

a state-by-state

database of available mental health services in the U.S., or try

www.rethink.org for services in the U.K.

What is the prognosis? How likely is it that

a person with schizophrenia will ever have a "normal" life?

With treatment, rehabilitation therapy, and lots of social support

and understanding, many schizophrenia patients can recover to the point

where their symptoms are more or less completely controlled. Many are

living independently, have families and jobs, and lead happy lives.

See the success

stories of some such patients on the schizophrenia.com website.

One schizophrenia.com member had the following to say about living with

schizophrenia:

"Those early years when you are first diagnosed are very

hard. Many people are very surprised by the illness and don't know

what to do. Many refuse medicines. But as time goes on, most people

learn what works. They find their best medication. They find a way

to live that is satisfying and doesn't stress them too much. They

learn not to drink too much alcohol, and to take care of themselves.

The find a good doctor, and often others help them, such as friends,

priest, or counselor. People make a decent life for themselves. They

find love, ,they find work....it gets better. The key is to stick

with the medication, and to never give up."

However, although research has made great strides in both understanding

and treating the disorder, there is still much that we don't know. We

still don't know why some patients deteriorate faster than others, why

some don't respond to medication as well, why some make good recoveries

while others are unable to. It's important to realize that while there

are lots of things that the patient and the family can do to help the

prognosis, schizophrenia is a disease that sometimes takes its own unexpected

course. Setbacks are to be expected, and are not signs of failure on

anyone's part. It's important to set your own expectations and goals

(whether you are the person suffering from schizophrenia or a caregiver)

to an achievable level, and appreciate accomplishments for what they

are rather than what they're not. One schizophrenia.com member pointed

out that everyone's "climbing the ladder" of life, but someone

who starts from the bottom and manages to climb up halfway has achieved

a lot more than someone who starts at halfway but only climbs a rung

or two.

There are factors in the course of the disease that can, to a certain

degree, help predict the various outcomes. You can improve the chances

for a good prognosis by knowing

what the indicators for possible relapse are, working to get the

best possible treatment as quickly as possible, and learning how to

effectively self-manage a long-term mental illness. The mentalhealth.com

website also has information on what

family members can do to help ensure the best possible outcome.

For a good presentation on the prognosis for people who have schizophrenia,

and an update on new treatments for schizophrenia see the Stanford

University "New Treatments for Schizophrenia" presentation.

How is schizophrenia treated?

American Psychiatric Association's

Guideline For The Treatment Of Patients With Schizophrenia states:

"antipsychotic medications are indicated for nearly all acute psychotic

episodes in patients with schizophrenia." In addition to antipsychotic

medications, some patients also take anti-depressants or mood-stabilizers

to help control related symptoms.

Medications work successfully in the majority of patients (approximately

70% of patients will improve, according to research - but we've also

seen research that suggests the chances of any one drug working for

a person may be only 50% so people frequently have to try more than

one drug to partially or completely control the positive symptoms (hallucinations,

delusions, paranoia, racing thoughts, etc). They are not as effective

in controlling negative symptoms, and may cause side-effects of their

own. See our Medications

area for information on commonly prescribed antipsychotic medications

- how they work, how effective they are, what side-effects they cause

- as well as additional info on research studies and medications in

clinical trials. See also New

and Newer Mechanisms of Action for Antipsychotic Medications, an

online UCLA grand rounds video presentation that explains (in some detail)

what areas of the brain different drugs target, and what effects they

have.

For a good presentation on the prognosis for people who have schizophrenia,

and an update on new treatments for schizophrenia see the Stanford

University "New Treatments for Schizophrenia" presentation.

Although an important element, medication is far from the only treatment

used for schizophrenia patients. Many patients and their families choose

supplemental therapies (these can include psychosocial or cognitive

therapy, rehabilitation day programs, peer support groups, nutritional

supplements, etc) to use in conjunction with their medications. In certain

severe cases, some patients also respond to electroconvulsive

therapy (which has been shown to be safe and effective) or transcranial

magnetic stimulation (TMS).

In the case of therapy, some research has shown that psychotherapy

and medication can be more effective than medication alone (however,

the same study noted that psycotherapy alone was NOT a substitute for

medication). The three main types of psychosocial therapy are: behavioral

therapy (focuses on current behaviors) cognitive therapy (focuses on

thoughts and thinking patterns) and interpersonal therapy (focuses on

current relationships). For schizophrenia, cognitive-behavioral therapy

has shown the most promise in conjunction with medication.

For some supplementary treatments options (as well as "alternative

therapies" that have been disproved), see Other

Treatments on the schizophrenia.com homepage.

For more information, see Treating Schizophrenia - What Are the

Options? (ABC News webcast). ABC news host talks with a panel of

experts about what treatments are out there and how successful they

are.. Link

to video file and transcript. (If

you don't have it, Download Quicktime video player.)

What to expect after going on medication:

Medication can greatly decrease symptoms and help a person return to

a functional level; however, every case is unique, and medications are

not perfect. It will likely take a long, frustrating trial-and-error

process before a treatment regimen is found that works best for the

patient.

When a psychiatrist prescribes any medication, ask what symptoms it

primarily treats, what the common side effects are, what dosage he/she

is prescribing, and how long it will take to start working. Keep track

of every medication (and at what dosage) you (or your loved one) is

on, what side effects it causes, which symptoms get better and which

get worse. A journal (the same journal where you write down symptoms

and behaviors) is an excellent place to do this.

Don't be surprised if the doctor keeps switching medications, or adjusting

dosages. They are not frivolously experimenting; trial-and-error is

the only way to eventually find a combination that works. Medications

are never a perfect fit: a prescription can work for awhile and then

stop working, or one that you tried previously may work at some point

in the future. You can help this process with feedback about the different

medications (see paragraph above).

An antipsychotic medication can take weeks or even months to start

working at full strength, so be patient and keep recording things in

your journal. Medications are less likely to make any huge, noticeable

changes in life; instead they should make things generally "easier."

Once you find a medication that seems to work, the voices/hallucinations

may gradually fade away and disappear - or they may not. Sometimes these

voices quiet down to a point where they are not harmful or debilitating,

and many people with schizophrenia make a decision at this point that

living with these quieter voices in the background is preferable to

going through the pain of more medication and more side-effects.

Some general things to be aware of:

Both the illness itself and many of the medications used to treat it

can make a person feel overly tired or lethargic. You may need to sleep

more than you think, and it may be unrealistic to try and dive head-on

back into your normal activities. Recovering from schizophrenia is like

recovering from any long-term illness. Plan small goals to ease yourself

back into a routine that you enjoy, and don't expect too much of yourself

at first in terms of socializing. Be aware if others are pushing you

too hard to "get back out there" - give yourself the time

and support you need.

What if I can't afford prescription medications?

Without a good health insurance plan, antipsychotic medications (particularly

the newer ones) can be terribly expensive. However, you have some options

even if you are currently unemployed or uninsured. Here are a few suggestions:

- Apply for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or disability benefits,

federal funds that are available for physically or mentally disabled

persons who are unable to work. See Schizophrenia.com's Help

with SSI page, or the Social Security

Association website for more info on programs and how to apply.

- See if you qualify for Medicare (for elderly) or Medicaid (for low

income persons) health coverage. Your doctor or a hospital social worker

can advise you on your eligibility, and help you apply. See also

"Living With Schizophrenia - Practical Matters" in this

FAQ guide for a list of federal aid programs for disabled or low income

persons.

- The older antipsychotics tend to be cheaper than the newer ones -

discuss with your doctor the possibility of using a cheaper alternative.

Be aware, though, that the older medications also may have significantly

more side-effects, and are not as effective controlling negative symptoms

- Information

on available low-cost medications, and what benefits are available

to mentally ill or disabled persons, is available on the schizophrenia.com

website

Finding and Working with the psychiatrist:

A good psychiatrist can and should be an ally in the continual process

of treatment and recovery. They should be willing to work with you as

an informed member of the treatment team and ideally they should be

well-informed and experienced in treating schizophrenia and related

disorders. Here are some suggestions to help you find a psychiatrist

you can effectively work with:

Hospitalization - when and why is it necessary?

At some point or another, most people with schizophrenia will likely

have to be hospitalized for at least a short time. Hospitalization can

be voluntary (requested by the patient themselves) or involuntary, meaning

it is up to the discretion of the treating psychiatrist, emergency room

staff, or a courtroom (see

the criteria and procedures for involuntary hospitalization by U.S.

state). At the point of hospitalization, a person may be in pretty

bad shape - feeling sick, scared, out of control, and abandoned. Understandably,

at the time it's not a pleasant experience for anyone involved. But

it doesn't have to be something to fear.

Why might somebody need hospitalization, rather than outpatient

care?

- patient needs to be in a protected environment to keep them from

harming themselves or others.

- patient needs to be monitored by trained professionals for symptoms

and medication reactions.

- patient needs a safe place where they can stabilize and concentrate

on recovery.

- family needs a short respite to gather themselves and make long-term

treatment plans.

What can you get with hospital treatment that you can't get as an

outpatient?

- constant monitoring in a controlled setting, so medications can

be adjusted more quickly and accurately. Hopefully, this means you

start feeling better sooner.

- more time with a doctor and/or therapist, maybe every day. Trained

staff members are always around to talk to about questions, concerns,

or thoughts.

- group therapy, recreation programs, vocational/social rehab (programs

will vary depending on the hospital)

- A safe place to gather yourself, get settled with medication, and

stabilize so you can return to your own life as soon as possible.

- according to one schizophrenia.com member: "plenty of rest,

free food, free laundry, you get to meet nice people, free recreation,

[and] you get a chance to draw pictures and watch a show or two."

Many members of schizophrenia.com have written

about their experiences in hospitals (either voluntary or involuntary)

on the discussion boards. Most agree, at least in retrospect, that getting

treated in the hospital was the best thing for their health and well-being

at the time. Some of their thoughts are quoted below:

"It's nothing to be scared about. Try the meds they give

you and work with the staff. They are there to help and want you to

talk to them when you are having problems. The other patients on the

ward will have different illnesses than just schizophrenia, like bi-polar,

depression and drug addiction...Hopefully if you go you can get things

straighten out."

"I found that I was at my worst the two times I was at the

hospital. So I did not like being there at all. But it was a place

where I was safe, a place where I couldn't hurt myself or wander off.

The hospital is the place my healing started, and I find that it was

not an enjoyable experience but a helpful one."

"[T]he better your attitude about being hospitalized and

the more hope you have for yourself, the better you will do, I think.

I had faith that the medicine would help me from the beginning, and

it turned out to be true."

"[S]ometimes, as my pdocs have said over the years, we need

a "safe place" and sometimes that is the hospital."

Once it has been determined that hospitalization

is necessary, you may have a choice (depending on insurance, availability,

and your psychiatrist's recommendations) of what hospital to go to.

Psychiatric facilities include public hospitals (state, county, or community),

university (teaching) hospitals, private psychiatric treatment centers,

and VA hospitals. Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, in his book "Surviving

Schizophrenia" (pp. 180-188)offers the following suggestions

for evaluating psychiatric in-patient facilities:

- talk to your doctor, treating psychiatrist, hospital staff, and

other families who are familiar with programs in the area; ask for

their recommendations and reviews of various programs

- look for a Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations

(JCAHO) accreditation. A JCAHO team, upon invitation by the hospital,

surveys patient care and services, therapeutic environment, safety

of the patient, and quality of staff and administration. The hospital

may receive full 3-year accreditation, full accreditation with a contingency

(meaning that a follow-up inspection may be warranted), or no accreditation.

Bear in mind that accreditation is given to hospital as a whole,

NOT to individual wards. Ask for JCAHO accreditation at the hospital

administration office, or look for a certificate by the entryway or

in the lobby.

- the quality of staff, first and foremost, should indicate the quality

of the ward. Due to the staff, even individual wards in the same treament

facility may vary in quality.

- do NOT assess quality by fees charged. Private facilities are not

necessarily better than public ones. Again, evaulations of the staff

at each location should guide you.

Hospitalization is no easy experience for friends

or family members either. Especially if commitment was involuntary,

family may be hesitant about visiting, unsure of how to react when their

loved one returns home, and fearful that their loved one will never

forgive them for making that hard choice. One schizophrenia.com member

had the following thoughts about committing her child:

"In the early years, I would grieve myself so badly I would

get physically sick. I felt so much guilt if I allowed myself the

slightest amount of pleasure, so instead would stay in continuous

grief mode. It consumed me day and night - all I could think of was,

what was what my child going through at that very moment? What kind

of a Mother could I be if I dared allow myself to read a book, go

to a movie, etc. when my son was locked up...

This I tell you serves no purpose. You need to be kind to yourself

right now. Enjoying a bubble bath, going window shopping, having a

laugh, does not mean you do not care and are not concerned. Instead

it enables you to focus on helping your child and keeping up your

spirits so you can show them a positive attitude."

Keeping a positive attitude, even through the difficult experience

of hospitalization, is something that many family members stressed as

important. As one relative said, "It's so important to be cheery

& positive when you visit them in hospital. I found it helped a

lot if I just talked as if I EXPECTED him to be better soon."

Some family members are unsure about visiting, not knowing what to say

or if their loved one even wants to see them. Visiting might indeed

be difficult until medications start working - the ill person is not

feeling well, and may be angry, frightened, or even out-of-control.

In retrospect, most people who were committed agree that they needed

to be hospitalized at the time, and appreciate that someone was looking

out for them. Even if your loved one refuses to see you, or is angry

with you, showing your love and support by continuing to go is one of

the best things you can do. It helps to get through to them, even subconsciously,

that they have not been abandoned. Below are thoguhts on visiting from

schizophrenia.com parents:

"He hated us for putting him in there.... until the meds

kicked in. (He was never happy we did it, but never held a grudge

that we did.) We went each evening after work all the way to the hospital

to see if he would visit with us. The answer was always no, so we'd

turn around and head for home. But we went anyway. The reason? Because

we felt (and so did the psychiatrist we had then) that deep inside

that pile of rage and paranoia was our son. And that deep down inside

he needed to know that he was loved. So we went, were turned away,

and did the same the next day or so, until the meds had kicked in

and he wanted to see us."

Other things family members can do to make the hospital stay as easy

as possible:

- Get to know the ward staff, so they know that someone is actively

interested in the welfare of that particular patient. These are also

the people who will ultimately be able to explain to you what is going

on with your loved one, and help address your questions and concerns.

- Arrange for a tour of the facility, and become familiar with admissions

procedure, daily schedules, and visiting hours and regulations.

- Ask about any rules regarding bringing a patient gifts, photographs,

or food.

- Ask to be notified when your loved one is getting ready to be discharged.

- Learn about the treatment plan, and find out what your role in it

can be.

- Talk with the staff before your loved one is discharged about how

to continue care at home, what signs might signal a relapse or a mdeication

reaction, and how to make the transition to living at home as smooth

as possible for everyone.

The following online resources have more information about the logistics

and experience of psychiatric hospitalization:

--involuntary commitment

- another section of the FAQs, deals with procedures for commitment

and common fears/concerns of loved ones making the decision.

--Let's

Talk Facts about Psychiatric Hospitalization (APA publication).

--Psychiatric

Inpatient Experiences - a personal voice on what psychiatric hospitalization

is like, and advice to make it a more positive experience.

--a public radio show about

mental hospitals (particularly Bellvue in New York)

--Psychiatric Hospitalization:

What It's Like on the Inside (radio program)

--Returning

Home - an online booklet for families about helping a loved one

transition back into the home environment after spending time in a psychiatric

facility.

My son/daughter or brother/sister is over the

legal age of 18 and the doctors won't share with me information on his

treatment (due to current laws). How can I make sure my son/daughter is

getting the best possible treatment and the doctor is well informed?

While doctors and nurses "BY LAW" are not allowed to talk to

you about the situation with your son/daughter or brother/sister if they

are over the age of 18 (in most states). Many doctors and nurses are sympathetic

to the challenges the family faces - but they have to follow the law or

they could lose their jobs.

The doctors are, in most situations, required by Law to tell the patient

if they talk with you, and generally cannot talk with you - but the tip

here is that a lot of smarter and more compasionate doctors know of the

challenges that families face and so "bend" the rules a bit.

In a recent presentation by a psychiatry doctor at one of the top medical

schools in the US said that what she would do is accept phone calls from

family members and let them talk to the doctor (her) - and listen to the

family member (for example to let the family member tell the doctor of

what the behavior was at home recently, the delusions, actions, etc. -

for example if the ill family member is in the hospital for a 72 hour

hold and the hold is about to expire - but the doctor would not "speak"

back to the family member who was calling - just listen. This woman said

that if she got such a phone call she would quickly add another 72 hours

to the hospital "hold" to help give the ill person time to start

working towards recovery.

So - if you call the doctor, and tell them that you know that they can't

talk to you - but if they just hold on to the phone so that you can tell

them some things, that you don't think that this would be breaking the

rule of patient confidentiality...

Of course - every doctor is different.

If the behavior of the family member is potentially violent or dangerous

and the hospital or doctor is not being responsive in a way that you think

is best for your son or daughter (or sister or brother) then you may have

to let the doctor and hospital know (in writing) that you will hold them

legally liable for anything that happens because they are not doing their

job and treating the mentally ill person. See: How

to Force the System to Give You or Your Family Member Better Care

for more information.

And yes - in our view its a very stupid law that prevents a parent from

helping and being involved in their mentally ill son's or daughter's treatment;

its a legal response designed for situations where the person is mentally

capable, not mentally ill. These laws make it very difficult to get help

for your mentally ill family member, and difficult to understand how to

best help the mentally ill family member (who is frequently living in

the same house!). You can work to change the system to make it easier

for families to get treatment for the people who need it - by contacting

the organization called the Treatment

Advocacy Center.

How can I help my loved one get the best care possible?

It can be frustrating working within the modern healthcare system.

Especially in the middle of a crisis situation, when everyone is stressed

and frightened, it can seem like no one is paying attention to your

or your loved one's needs. However, there are many things you can do

to communicate effectively and get the care you need and deserve. Here

are some resources to help:

1) Make sure the doctor/psychiatrist is aware of all the symptoms -

if they don't have all the information, they might be led to an incorrect

diagnosis. Keeping a

symptom journal is the most thorough and accurate way to do this.

2) Become familiar with the treating psychiatrist, the nurses at the

hospital, the social workers, and anyone else directly involved with

your relative's care. These are the people who should have your loved

one's best interests and welfare at heart, and the people you should

go to if you have questions, concerns, or complaints. Be assertive -

you have every right to know what is going on, and have things explained

to you in a way you understand - but be polite and flexible also. Too

many times hospital staff get impatient with "problem" family

members who they see as rude or demanding. It's vital to have a good

working relationship with the treatment team.

3) Be polite but persistant in your quest to get information and answers.

Hospital staff members are inevitably busy, but they are there to give

the best care possible to consumers and their family. Keep your conversations

and requests short and to the point, to maximize the time they have

for you. If they are unable to see you, leave a message with your name,

your relative's name, and your number, and keep the phone line clear

so they can reach you at the first opportunity. Consider putting your

question or request in a letter, and delivering it to their office.

Remember to write down things you appreciate - special considerations

or care that you or your relative recieved from a care provider - as

well as concerns.

4) If you are an immediate relative or caretaker, make sure that you

have clearance to speak with the psychiatrist and other doctors about

the diagnosis and treatment plans. Current confidentiality laws prevent

doctors from speaking with anyone other than the patient (assuming the

patient is a legal adult), unless the patient gives their official permission

with a HIPPA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliancy

form. It can be absolutely essential for another person (a family member,

primary caretaker, etc) to be informed of treatment decisions, especially

because so many people with schizophrenia have very little insight into

their own illness. Getting confidentiality clearance ahead of time can

prevent many battles in the future over treatment compliance. See 'Involvement

of Family Members in Treatment Plans for their Hospitalized Relative'

for more ideas.

5) See 'How

to Get Better Care' for ideas on how

to work cooperatively with the hospital staff and the treating doctors

to improve care.

Why won't my loved one stick to their

treatment? How can I convince them to take their medication without upsetting

them, or making them feel like I'm the enemy?

According to schizophrenia expert Dr. E. Fuller Torrey ("Surviving

Schizophrenia" 4th ed, p. 295), there are several reasons that

people with mental illnesses refuse or stop treatment (also known as

"medication noncompliance). These reasons include:

- Lack of insight into the illness (also called anosognosia - a biological

symptom of the disease)

- Denial (a psychological issue - person is aware of illness but wishes

not to be ill)

- Medication side-effects

- Poor doctor-patient relationship

- Delusional beliefs about medication (e.g., that it is poison)

- Cognitive deficits, confusion, disorganization

- Fears of becoming medication-dependent or addicted

Some of these reasons are easier to deal with than others; for example,

you always have the option of finding a better doctor, or adjusting

medications to reduce side effects. Providing the patient with information

about their illness (the benefits of medication, the long-term prognosis,

etc) has been shown to improve compliance.

Simplifying the treatment regimen with single daily doses, use of compartmentalized

pill containers, long-acting injections, etc. can also help.

Unfortunately, one of the most difficult reasons for medication noncompliance

is also one of the most common - statistics estimate that 40% of schizophrenia

patients lack insight into their own illness as a symptom of the disease.

Such anosognosia makes an enemy of anyone who tries to convince them

otherwise. There is sometimes no way to force compliance without long

and upsetting battles with your loved one. However, medication is currently

the best tool we have to control psychotic symptoms and improve patient

insight. Many members of schizophrenia.com have indicated on the discussion

boards that living with schizophrenia is difficult enough with

medication; without it, it's downright impossible.

You do have options available to you. Assisted Treatment is a benign

term for an extremely difficult task - to help (or 'assist') a loved

one with their treatment because they are unwilling or unable to take

care of themselves. Assisted treatment options may include benevolent

coercion, obtaining conservatorship or guardianship, conditional release,

outpatient commitment, or involuntary commitment. The Treatment Advocacy

Center website has excellent information

and resources on Assisted Treatment.

A less extreme technique suggested by other schizophrenia.com members

is to ask your loved one to try the medication for a specific period

of time. Hopefully, once the medication starts to take effect, the person

will begin to regain some rational thinking skills, and you start to

talk reasonably together about the benefits of long-term treatment.

However, make sure you give the medication enough time to work - it

can be at least 1-2 weeks before any improvement is noticed, and many

antipsychotic medications don't take full effect for weeks or months.

Others at schizophrenia.com have come to the extremely difficult point

of offering their loved one an ultimatum - either get treatment and

stay med compliant, or someone is going to leave (either you, or the

patient). Another similar method of coercion is to stop supporting your

relative financially unless they agree to treatment. There is no way

to know or guarantee the results of such an ultimatum, so consider carefully

if you are willing and able to follow through with your threat. It will

only work if you are committed to carrying out your words. Also consider

carefully your own safety and the safety of your family before making

such a threat, since the illness can make some people behave unpredictably

or violently, even against someone they love.

For more ideas and resources for dealing with the difficult subject

of treatment compliance, see the following:

Coping With Schizophrenia:

How do I understand and deal with the symptoms?

Each case of schizophrenia will have a unique combination (in terms

of severity, duration, prominence, etc) of positive, negative, and other

symptoms. Related conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders,

and mood-swings are not uncommon either.

One schizophrenia.com member diagnosed with the disease described his

symptom experience with the following words:

The things that I have that I wish I didn't have are hallucinations,

delusions, and loss of thought control.

The things that I don't have that I wish I did have are curiosity,

motivation, and sex interest.

The above is pretty much the way schizophrenia goes.

Many family members struggle to understand what their loved one is

dealing with, and want to relate and empathize with their illness experience.

One of the best ways to understand what is behind some of the common

symptoms of schizophrenia is to educate yourself as much as you can.

"Surviving Schizophrenia" (Dr. E. Fuller Torrey) and "I

Am Not Sick! I Don't Need Help! (Xavier Amados) are two books repeatedly

recommended by veteran families on schizophrenia.com for people searching

to better understand the experience of mental illness. Other

recommended books, videos, and websites can be found on the schizophrenia.com

website.

Some general materials to help you live and cope with the symptoms

of someone diagnosed with schizophrenia include:

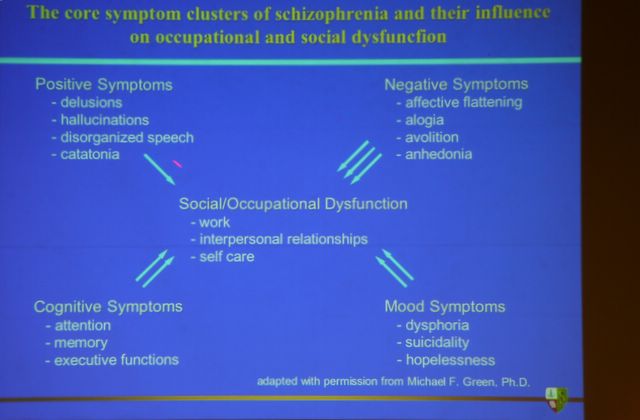

Source: Presentation

by Dr. Ira Glick,"New Schizophrenia Treatments" - Stanford

University Schizophrenia and Bipolar Education Day, July 2005

(Click to see full presentation) Explanation of Terms:

Delusions are fixed inaccurate beliefs, hallucinations are seeing or

hearing things that are not actually there, Catatonia is an abnormal

condition variously characterized by stupor, stereotypy, mania, and

either rigidity or extreme flexibility of the limbs, Affective Flattening

means that a person with schizophrenia will tend to have a flat emotion,

or be emotionless much of the time, Alogia

is the inability to speak, Avolition is a lack of motivation or desire,

Anhedonia

is the inability to experience pleasure. Dysphoria is

an emotional state characterized by anxiety, depression, or unease.

Executive functions are the brain's thought processing abilities that

allow people to plan and problem solve (and which are typically significantly

decreased by schizophrenia).

The following are specific suggestions that schizophrenia.com members

have posted on the discussion boards concerning some common symptoms

of schizophrenia and their associated problems.

Delusions: The common categories

of schizophrenia delusions include persecution delusions (feelings that

you are being spied on, conspired against, cheated, drugged, or poisoned),

jealousy delusions (a feeling without just cause that your loved on

is unfaithful), and self-importance delusions (also known as delusions

of grandeur - the feeling that one has a great but unrecognized ability

or talent, or the belief that you are an exalted being. Sometimes these

have a religious flavor to them). It's upsetting and frustrating (to

put it mildly) to be the victim of such delusions, especially when your

only goal is to love and support your ill relative; however, the closest

family members and relatives are often the first targets of this and

other hurtful behavior.

Due to the disease, a person with schizophrenia often can't think or

reason rationally. Explaining logically why the accusation can't be

true won't work, and will ultimately be draining and frustrating, due

to this fact. Try talking directly with the psychiatrist about the delusional

symptoms - the current medication may not be adequate to control them.

Also, be aware that delusions can take weeks or months to fade, even

if the person is medication compliant.

Voices/Hallucinations: The experience of

hearing voices or seeing visions are as real as anything else to the

person with schizophrenia. Like delusions, it usually does no good to

try and refute them. On the other hand, it's also not a good idea to

just "go along with them," which ultimately doesn't help anyone.

Family members who have tried to support their loved ones in the search

for "them", or tried to keep "them" out with elaborate

security devices, have only ended up frustrated. There are no lock to

keep out invaders in your mind; no matter how hard you search, "they"

will always be there.

One thing you can do is to simply acknowledge that your loved one is

experiencing something unique to them - you can say "I'm sorry

it's bothering you" or "why don't you tell the doctor about

it," which doesn't ignore their experience but also doesn't give

false evidence that others can see or hear these things. Sometimes the

best thing that family members can do is encourage the ill person to

write down/remember their experiences, and discuss them with their doctor.

Anger/Irritability/Mood Swings: Try to steel

yourself internally; recognize that this is the illness talking, not

the person. Some people have tried a detached, non-reaction to their

relatives' anger; others have waited for the episode to pass (or calmed

themselves down by going for a short walk) and then communicated how

much they were hurt by that behavior. If mood swings are severe, a mood

stabilizer might be beneficial. Talk to the doctor about possible options.

Violence or Abuse: Call 911 or the emergency

room and get help. Your first obligation is to yourself, your own safety,

and the safety of other family members. If you truly feel that you are

in danger, if you have ever been hurt or seriously threatened, convince

the authorities any way you can of the seriousness of your situation.

Do not accept a diagnosis of schizophrenia (or anything else) as an

excuse for this kind of harmful behavior. The disease may affect a person's

thoughts and perceptions, but abuse is still abuse. What you need is

not just action for domestic abuse, but an involuntary commitment to

a treatment center and a psych evaluation.

Paranoia: See 'How

to Manage 5 Common Symptoms of Schizophrenia', which has 6 steps

for dealing with paranoia. Try to know and avoid situations that overstimulate

or ovewhelm the person - too much sensory input at once can contribute

to paranoid or delusionary symptoms.

Suicidal Thoughts and Tendencies: Suicide

is a real and tragic consequence for many schizophrenia patients - about

40% will make at least on attempt, and between 10% and 15% actually

succeed in killing themselves. A major factor is depression, which is

a common companion of schizophrenia disorders. See 'Managing

Depression' for further information on this topic, or the section

on depression further down in this FAQ guide. If your loved one seems

depressed, you can ask the psychiatrist about the possibility of taking

an antidepressent medication in addition to antipsychotics.

Family and friends can help by being very aware of depressive and suicidal

tendencies, especially in those individuals recently recovering from

an episode or a relapse. See 'Preventing

Suicide' for warning signs and actions that you can take to prevent

a tragedy. If

you are currently thinking about suicide, please read this first.

Know the places you can call on quickly for help - find the crisis centers

in your area and know the services they provide. Contact local NAMI

chapter and ask them about such services.

Apathy/lack of motivation: Although many

people believe that these sorts of behaviors are due to medication side

effects or a lack of will on the part of the patient, most often they

are simply another symptom of the disorder. (Excessive apathy - i.e.

sleeping all day - may be a medication side effect that is compounding

the disease symptom. Talk to the psychiatrist about the possibility

of adjusting meds). The current generation of antipsychotic medications

are much better at treating the positive (psychotic) symptoms, but have

not made major headway against the more cognitive/behavioral negative

symptoms. When you consider that schizophrenia severely disorders the

way an affected individual senses and perceives the world, it's easier

to see why that person might stridently avoid any sort of stimulation,

even just going out to a mall or riding on a bus. One schizophrenia.com

member suggested a comparable situation: two guys are climbing a mountain,

but one is carrying a backpack full of tennis balls and one is carrying

a backpack full of rocks. It may seem that the one is lazier for not

going at the same pace, but he's got a heavier burden to carry.

One of the best ways to help is to actively pay attention to your loved

one's responses. If they respond positively to your overtures or your

attempts at conversation, by all means continue. If you feel rejected

or rebuffed, remember that it is most likely a protective mechanism

against too much sensory overload; stop and try again later. Establishing

small routines or rituals can be very helpful, and a good source of

shared time.

Emotional flatness or social withdrawal: Many

family members are hurt by a feeling that their loved one is emotionally

withdrawing into themselves, and that they just don't relate or interact

anymore to the people around them. Emotional withdrawal/flatness is

one of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Some of the newer antipsychotic

medications can help alleviate these negative symptoms; however, they

are not 100% successful, and the response is different from every patient.

One member described his emotional responses in the following way:

"As a schizophrenic I will tell you that my emotions are not just

hard for the world to access, sometimes it is also hard for me to access

my own emotions."

Schizophrenia patients often have trouble with common social cues that

most people do and recognize without thinking - body language, eye-contact,

gesturing, varying the tone of the voice, etc. They don't realize they

are missing these basic cues, and their absence can make the person

seem much more withdrawn and cold than they intend to be. 'Coping

with schizophrenia: social deficits' from mentalhealth.com has good

explanations and suggestions for dealing with this.

Experienced members suggest finding other emotional outlets for yourself

- make time to go out with other friends or just you, and spend another

time with your loved one. Another thing you can do is specifically bring

to the person's attention the fact that you want to share something

with them. Sometimes you may have to simply, lovingly, request their

love and attention.

How Can I Help Someone Who's Depressed? How

Common Is Depression in Schizophrenia Patients?

According to the president of the 20th Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum

(CINP), comorbid mood disorders (such as depression) are so prevalent

in this patient group that they may be considered a fundamental characteristic

of schizophrenic disorders. Up to 80% of schizophrenia patients experience

serious depressive symptoms.

There are several reasons why a person with

schizophrenia is more likely to experience depression than the average

person. Depression may be a biological symptom of the disease - one

of the negative-category symptoms like apathy. This can be compounded

by the extra burden of stress carried by someone living with a chronic

disease. Depression or mood-blunting might be a side-effect of an antipsychotic

medication (abilify and risperidol are two that schizophrenia.com members

have indicated can cause depression). Depression might be a co-diagnosis

along with schizophrenia - some of the same neurotransmitter imbalances

that are implicated in schizophrenia may also contribute to the development

of depression. Finally, depression may be the major diagnosis - for

example, if a person has manic depression, or major depression with

psychotic features. These patients still experience hallucinations and

delusions; however, they tend to have a characteristically negative

tone (for example, a person might believe he/she will cause the world

to end, or he/she is guilty of some unforgivable crime).

Likewise, depressive symptoms can appear at various points during the

course of the illness. Many patients who experienced depression before

starting on a treatment program reported that their depressive symptoms

initially faded with the start of antipsychotic treatments, but then

returned once the positive symptoms stabilized. There could be both

a biochemical and a psychological factor to this. As visions of grandeur

and self-importance, ideas of divine missions, and voices that have

been constant companions for years begin to slip away, many people understandably

feel lonely and isolated. They are frightened as they wake up to a new

"real" world that is unfamiliar and difficult to navigate.

Says Dr. Wingerson (psychiatrist) in Rosalynn Carter's book 'Helping

Someone with Mental Illness': "To be psychosis free with nothing

to look forward to can be devastating" (p. 141).

Regardless of the cause, depression is important

to treat, especially given the high rate of suicide among schizophrenia

patients. Moreover, research has indicated that depression has a profound

effect on quality of life, irresepective of the presence of other schizophrenia

symptoms. "Quality of life among people with schizophrenia may

be more closely related to levels of anxiety and depression than to

the core symptoms of the disorder such as hallucinations, delusions,

and anhedonia" ("Quality

of life in schizophrenia: contributions of anxiety and depression."

Schizophrenia Research, 2001:51(2-3):171-180).

Schizophrenia.com members suggest the following to help deal with depression:

- write your feelings/thoughts in a journal to share with your psychiatrist

or a family members/friends, so someone knows how you are feeling

on a daily basis

- try not to isolate yourself. If you're not feeling up to socializing

or talking face-to-face, a good alternative can be reaching out through

emails, chatrooms, and discussion boards. Many members say that peer

support groups are invaluable to them.

Says on member, "I was an isolationist for a long time, and it

only contributed to the depression and negative symptoms I experienced.

You need to have someone you can talk to, whether it's through a support

group, friends, or an online forum."

- ask your psychiatrist about starting an antidepressant medication.

Many schizophrenia patients take an antidepressant in addition to

anti-psychotic meds. Common options include: SSRI medications (Prozac,

Celexa, Paxil, Zoloft, Lexapro), Effexor, Venlafaxine, Wellbutrin.

Remember to give the meds a month or two to take full effect - see

"What

to Do for 6 Weeks While you Wait for Antidepressants to Kick In"

for coping strategies in the meantime. Also, be aware that your body

might get "accustomed" to the medication. Let your psychiatrist

know if depressive symptoms return, so you can get your medication

adjusted or changed.

- Psychotherapy is one of the cornerstones (along with medication)

for schizophrenia and depression treatment. It helps improve day-to-day

functioning, social skills, quality of life, and motivation at the

same time that medication is improving chemical balances in the brain.

Moreover, studies have shown that psychotherapy causes similar alterations

in brain function to those seen with medication, although it only

seems to be effective in conjuction with medication therapy.

- Nutritional supplements have been shown to increase the effects

of antidepressent medications. Schizophrenia.com members suggest fish

oil supplements (omega-3 fatty acids) or folate supplements. See

research supporting the use of nutritional supplements with medication.

- Many schizophrenia.com members say that a regular program of exercise

keeps them feeling mentally and physically healthy, and helps combat

negative symptoms such as depression and anhedonia. Numerous studies

have shown that exercise induces a positive physiological reaction

in the body (increases B-endorphins and monoamine neurotransmitters,

decreases stress hormones such as catecholamines). Moreover, exercise

gives a positive sense of accomplishment, an increased belief in oneself,

and positive benefits for physical health. Walking, exercise videos,

and yoga are good easy activities for a beginning exerciser, require

little/no equipment or training, and can be done either by yourself

or with a partner.

- For severe depression, talk with a doctor about electroconvulsive

therapy (shown to be safe and effective), or transcranial magnetic

stimulation.

Some online support groups and hotlines for you to try if you are feeling

depressed or suicidal:

1. American Suicide Survival Line (888) SUICIDE or, (888) 784-2433. This

nationwide suicide telephone hotline provides free 24-hour crisis counseling

for people who are suicidal or who are suffering the pain of depression.

2. The Samaritans Suicide Hotline (212) 673-3000.

3. Covenant House Nineline (800) 999-9999

http://www.covenanthouse.org

This hotline provides crisis intervention, support and referrals for

youth and adults in crisis, including those who are feeling depressed

and suicidal.

4. Internet site: http://www.metanoia.org/suicide/

For those contemplating suicide.

5. Internet site: http://www.save.org/index.html

This is the Web site for SAVE (Suicide Awareness Voices of Education),

whose mission is to educate others about suicide and to speak for suicide

survivors.

More resources to help yourself or a family member who's depressed:

What are the chances of relapse? How can you plan for a relapse situation?

Medication may be controlling symptoms and working well for a long

time; however, even a correctly dosed antipsychotic will not totally

guarantee against an eventual relapse. Most medications claim to reduce

chance of relapse by about 80%. Be aware that additional medications

might be needed to specifically address anxiety, depression, or panic

attacks.

Dr. E. Fuller Torrey in his book "Surviving Schizophrenia"

identifies common signs and symptoms (ironically, the symptoms were

largely the same whether reported by the patient or by families) preceding

a relapse episode. These can include: tenseness and nervousness (of

either the patient or the home environment in general), trouble concentrating,

depression, trouble sleeping, loss of interest in things/enjoying thins

less, being overly preoccupied with one or two things (Surviving

Schizophrenia, p. 289). Both patients and families will learn over

time what individual symptoms tend to herald a relapse.

The family and living environment is key to the recovery process. A

low-stress, low-key emotional environment can reduce the chances of

relapse. Patients and their families can be aware of what is a high-stress

situation or environment, and take steps to avoid those things. It's

a good idea to have a straightforward plan to implement in a "get

worse" case, as schizophrenia is a very unpredictable disorder

and will naturally have its ups and downs.. Keep resources - people

you can call on, emergency numbers, lists of medications, etc - close

at hand. See Tips

for Handling a Crisis and What

Relatives Can Do to Help Improve the Course of Illness.

Consider discussing the possibility of an Advance

Psychiatric Directive, to help guide family members and healthcare

professionals during a crisis.

How do I explain the illness to family, close friends, and others?

First, decide who you want to tell (family and close friends who will

be supportive and understanding, who might be involved in the recovery

process) and who you need to tell (doctors, school administrators, employers).

Not everyone needs to know, and for the most part you can be as discriminating

as you wish about how much you disclose.

Once you've decided to tell someone about the illness, be proactive

about providing information - books, articles, internet links - that

will help them understand. Know that some people will be sympathetic

and supportive, and some will not. Schizophrenia is a hard disease to

deal with and understand, and some people are just unable to empathize.

Some members of schizophrenia.com suggest distancing yourself, to a

degree, from relatives and friends who cannot seem to understand or

be helpful. It's important to you and your ill family member that you

both stay as positive and as hopeful as you can about the illness.

Our online PDF reference library contains

documents that are ideal for printing and passing out to family, friends,

and others who you would like to share information with about schizophrenia

and mental ilness-related issues.

Living with a Severe Mental Illness - Practical Matters:

As with any other chronic illness, there are some practical matters

that caregivers and other family members will need to eventually deal

with. These might include:

- insurance problems and driving licences

- befriending and leisure activities

- finding appropriate accommodation with any necessary support

- sheltered employment and training for work

- benefits problems and debts

- legal rights and advocacy

- genetic counselling

- treatment, including medication and complementary therapies

- representation at tribunal, court or inquest

Know that you have resources to help you plan these matters. For example:

- Treating psychiatrist or therapist

- social workers at the hospital

- local community organizations for the disabled

- PLAN

(Planned Lifetime Assistance Network): developed to meet the needs

of families who are actively planning for the future of an adult child

with a disability. Programs (currently available in 22 states) help

families develop a future-care plan, establish the resources for payment,

and identify the person(s) or program(s) responsible for carrying

out the plan. May also provide current services that relieve parents

of part of the daily burden of care.

- In the UK: Rethink,

the largest mental illness charity in the U.K., has information

relating to medical, legal and financial benefits available.

The following is a list of federal aid programs and funding to help

people with mental and physical disabilities. (Source: Mental

Health, Mental Illness, Healthy Aging, a guidebook from the New

Hampshire chapter of NAMI):

Disability Benefits (SSDI): Benefits exist for workers who become

physically or mentally disabled prior to retirement age. Disability

must be severe enough to prohibit substantial work and be expected to

last for a year or more. Generally provides a higher income than SSI.

Supplemental Security (SSI): Provides monthly cash payment to

aged, blind, and disabled people who have little or no income. Recipients

may be eligible for Medicaid benefits. A handicapped child under age

18 may receive this if the child and parent meet income and resource

requirements. Those eligible for SSI may also be eligible for benefits

such as housing programs, Medicaid, vocational rehabilitation, and food

stamps. Children living at home (in some states) can qualify for an

extra benefit under "living arrangements", which is meant

to offset some of the costs of providing extra attention and care to

a special-needs child living at home. NOTE: Many people are denied on

their first application, but are later accepted through an appeals process.

See NAMI's

page on Social Security Benefits, with a list of questions and answers

such as who is eligible, how to apply, and what to do if an application

is denied. . See also Help

With US Social Security Insurance.

National Council on Aging: The National Council on Aging (NCOA)

has a website designed to help older Americans determine what federal

and state benefits and programs are available, depending on the individual's

circumstances and request. The website can be accessed at www.benefitscheckup.org.

Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled (APTD): Provides

financial assistance to persons determined to be medically disabled

and meeting financial need guidelines. Income and other assets are considered.

Eligibility guidelines are based on financial need and disability rather

than age.

Some thoughts on applying for SSI or SSDI from schizophrenia.com members:

What SSI needs to see is letters from several professionals who

have worked with the person, which state that he/she has a severe

and permanent disability, that has a name (either medical or from

the psychiatry DSM-IV, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th

edition), and that as a result of this disability she is unlikely

ever to be able to earn more than about $500 per month. Obviously,

to do this several things must be in place:

1) The ill person has seen a physician, psychiatrist, etc., been

examined, and found to meet criterion for such a diagnosis.

2) You must be able to communicate with the professional (with mental

illness this is next to impossible unless the ill person has filled

out a release of information form saying it's OK).

3) Tthe professional must agree to fill out the forms and write a

letter to SSI, and then actually do it.

Any person seeking SSI can have another person appointed to handle

all the paper work, etc. Be aware that the Social Security Administration

has a reputation for denying the first claim and the first appeal

(which is a paper review, that is almost always a rubber-stamped denial).

In seventy percent of secondary appeals, the decision is overturned,

and SSI is granted. The second appeal is heard in front of an Administrative

Law Judge, which in reality is not officially a "judge,"

but is a lawyer who specializes in administrative law. SSI will be

back-paid from the original application. A lawyer can really help

with this process, and many will take a percentage of the back SSI;

so there is no out-of-pocket cost.

The following are health insurance and aid programs for disabled or

low-income persons. (Source: Mental

Health, Mental Illness, Healthy Aging, a guidebook from the New

Hampshire chapter of NAMI):

Medicaid. Medicaid program helps pay for health care costs for

all persons who receive public assistance and for certain persons with

low incomes who can't afford the cost of health care. Criteria for this

program is the same as Aid to Persons Who Are Totally Dependent (APTD),

and persons receiving APTD may also qualify for Medicaid benefits. The

Old Age Assistance (OAA) program applies to individuals who are 65 years

and older.

Medicare: This federal health insurance program offers hospital

insurance coverage (Part A) and medical insurance (Part B) for people

65 and older who qualify for retirement benefits, for workers who have

been receiving disability benefits for 24 months or more, and for people

who need kidney and dialysis or transplant. There are various plans,

with some mental health benefits included. To apply, call 1-800-772-1213.

QMB/SLMB: This provision pays the portion of Medicare that covers

health insurance. Check with your local Division of Health and Human

Services office for more information.

HICEAS: This program provides health insurance counseling, education,

and assistance services to assist Medicare beneficiaries and their families

in understanding their insurance coverage and options. For more information:

1-800-852-3388.

Home Health Care: These are in home medical services for qualified

older adults in their home. Local visiting nurse or home health associations

usually provide home health care. Medicare may cover certain medical

and psychiatric services.

Lifeline: This is a personal response service for persons if